Xu-Bing e il potere della scrittura. Un’intervista

La riconoscibilità per un artista è spesso una questione di centrale importanza. Trovare un proprio linguaggio, uno stile che lo contraddistingua rendendolo riconoscibile tra i tanti, è ciò che ha reso celebri molti artisti, soprattutto negli scorsi due secoli. Ci sono poi coloro che non restano chiusi nella definizione di sé, nella ripetizione del proprio stile ad infinitum, ma che mutano in maniera quasi metamorfica. In questa esigua schiera figura senza dubbio l’artista Xu-Bing, tra i più noti e affermati artisti cinesi al mondo. Se certamente un fil rouge lega la sua ricerca e il suo processo artistico, guardandone il catalogo si può facilmente cadere in inganno e ritenere si tratti di opere di artisti differenti, tanta è la diversità di approcci, linguaggi, di tecniche e materiali impiegati. Xu-Bing ha infatti sviluppato una sorta di stile senza stile. Il suo lavoro attinge sia dal proprio passato personale che da quello arcaico del suo paese, dialogando anche con l’arte e il pensiero occidentali. È forse questo incontro tra Oriente e Occidente ad aver suscitato un consenso tanto unanime; l’opera di Xu-Bing è infatti ormai di casa nei principali musei americani ed europei (il Metropolitan e il British Museum tra i vari) ed è apprezzata da importanti filosofi occidentali come Derrida, con il quale ha tenuto anche una lezione a New York.

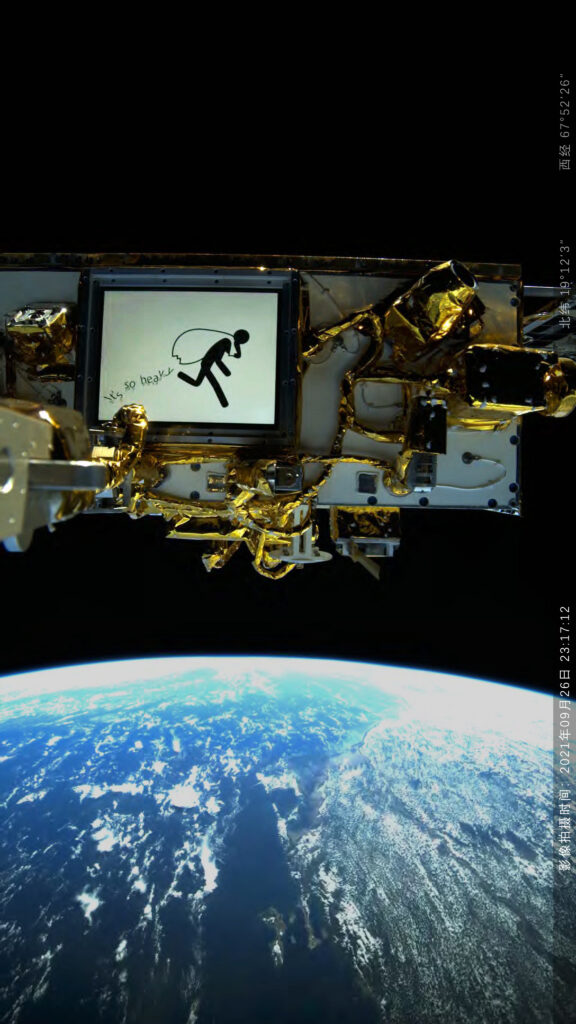

Abbiamo incontrato il maestro a Venezia nei primi giorni della LX edizione della Biennale d’arte, dove ha inaugurato la mostra personale “Art Satellite. The first animated film shot in space”, curata da Sen Fu con la collaborazione di Giovanni Argan e Yiping, visitabile fino al 7 ottobre nella chiesa dei santi Geremia e Lucia. Facendo eco all’iscrizione sul retro dell’abside della chiesa «All’Italia, al mondo, implori luce, pace», l’artista ha presentato nella Cappella di Santa Veneranda un’opera di videoarte avanguardistica e dal sapore futuribile, essendo infatti la prima in assoluto ad essere stata realizzata nello spazio. Si tratta di un breve video con un film d’animazione in stop-motion, proiettato su uno schermo del satellite Ladybug n. 1 mentre orbita intorno alla Terra. Il satellite, mezzo utilizzato soprattutto per scopi scientifici, militari e comunicativi, si fa per la prima volta strumento artistico, e andando oltre i confini terrestri, oltre le barriere e i muri, il problema del linguaggio tanto caro all’artista diviene universale.

Dopo alcune settimane abbiamo un appuntamento con l’artista a Roma, all’Accademia Americana, presso la quale ha inaugurato la mostra “A moment in Time: Xu Bing in Rome“ (curata da Ilaria Puri Purini e Andrew Heiskell) al termine della sua residenza presso l’istituto. Qui un calco della Muraglia cinese, realizzato dall’artista nel 1988 con la tecnica tradizionale del frottage, dialoga con un calco della via Appia eseguito appositamente per l’installazione, definita “The Wall and the Road (1988-2024)”. L’impero cinese e quello romano, le due grandi civiltà millenarie si incontrano, da un lato con la chiusura di un muro che serviva a proteggere, a cingere e delimitare, dall’altro con una strada, la “Regina Viarum”, emblema dell’apertura e dell’incontro con l’altro. Costruite a circa un secolo di distanza l’una dall’altra, a partire dal 214 a.C. dall’imperatore Qin Shi Huang la muraglia, e dal 312 a.C. la via per volere del censore Appio Claudio Cieco, la strada e la muraglia, ancora perfettamente conservate, sono prelevate nella loro pelle dall’artista. Isolati e visti da vicino, questi calchi hanno una loro dimensione autonoma e l’Appia, con le sue grandi pietre incastonate, sembra la pelle maculata di un felino e suscita un effetto quasi straniante, una reazione tipica a molte delle sue opere.

Due mostre aperte in contemporanea in Italia che danno la misura dell’importanza di questo artista, che ha fatto del linguaggio e del segno motivi di indagine e riflessione profonda con la sua ricerca artistica.

Nel giardino dell’accademia americana, mentre un temporale romba in sottofondo tenendoci in allerta, iniziamo la nostra lunga conversazione, passando dal cinese all’inglese all’italiano, con l’aiuto del giovane curatore Sen Fu.

Iniziamo parlando di uno dei temi principali della sua ricerca artistica: il linguaggio. La calligrafia cinese è una forma d’arte inserita anche nella lista del patrimonio immateriale dell’Unesco. Con la sua opera “Book from the sky” ha creato oltre 4000 caratteri cinesi inventati, molto simili a quelli reali, ingannando i visitatori. È stata una riflessione sul linguaggio? Sulla sua importanza, sulla capacità di influenzare la cultura e la società stessa?

Molte mie opere sono legate alla scrittura e al linguaggio. Non ho mai scelto o progettato questa cosa, è venuto da se’, in maniera naturale. La direzione che prende ciascun artista non è controllabile da lui stesso, né può essere davvero programmata. Avviene tutto per una sorta di predestinazione, di karma. A ogni artista non piace il proprio stile, il proprio linguaggio espressivo, ma ama quello degli altri. Il tuo linguaggio personale e il tuo stile, se ti appartengono davvero, non li puoi eliminare.

Se tu guardi la scrittura cinese, capisci la cultura cinese. Mia madre lavorava nella biblioteca dell’università, e io da piccolo vivevo lì dentro e guardavo i libri senza capire, affascinato però da questa scrittura. Quando imparai a leggere poi era il periodo della Rivoluzione culturale e non c’erano più libri che potevamo leggere, l’unico era il libro rosso di Mao. Quindi ho sempre avuto un contatto con i libri e le parole molto particolare. La scrittura ha avuto un grande potere nella storia dell’uomo; quando in Cina c’era l’imperatore, si potevano avere seri problemi anche solo per aver scritto una parola non gradita. Problemi che ebbe anche mio padre ai tempi della Rivoluzione culturale; quando ero piccolo ho visto il nome di mio padre comparire su un dazibao e su di esso c’era scritto che lui era un controrivoluzionario. Lì capii il potere della scrittura. Non a caso tutti gli imperatori cinesi quando salivano al potere la prima cosa che facevano era cambiare subito la scrittura. Quando cambiavano la scrittura penso cambiassero anche la mentalità e il pensiero delle persone.

In questo sforzo di comprendere qualcosa di illeggibile c’è un che di ironico, suggerito anche dal titolo dell’opera, che forse vuole evocare le sacre scritture? “In principio era il verbo”…

Questa mia opera ha una caratteristica che la contraddistingue: voglio che il filo del pensiero delle persone che la vedono si interrompa, che rimanga come bloccato, incastrato. Mentre si avvicinano al “Book from the sky” loro pensano si tratti di un monumentale libro con i suoi caratteri incisi che parla forse dei grandi temi della vita, ma poi non riescono a leggerlo, e in quel momento si iniziano a interrogare riguardo al libro e alla cultura.

Trovo di particolare interesse “A Case Study of Transference”, dove gli istinti più carnali erano messi in scena da maiali che cercavano di accoppiarsi, in contrasto con le scritte sui loro corpi e le scritte dei libri a terra.

È un’opera apparentemente molto diversa, ma in fondo molto vicina al “Book from the sky”. Mi è sempre interessata la performance, ma essendo molto timido mi sono avvalso di alcuni attori, in questo caso animali, e anche i caratteri sulla pelle del maiale non significano niente. L’aspetto più interessante sono state le reazioni che questi maiali che provavano ad accoppiarsi suscitavano sugli spettatori, che si vergognavano, provavano un forte imbarazzo, mentre per i maiali era tutto normale. Gli uomini hanno questi caratteri, ovvero la cultura, incisi non sulla pelle esterna ma all’interno del proprio corpo.

Con “Book from the ground” (2003) ha cercato di inventare da zero una lingua che tutti potessero capire con le emoticon, un sorta di esperanto universale. Come nasce questo libro?

C’è stato un periodo in cui ho viaggiato moltissimo, e passavo quindi molto tempo negli aeroporti, dove è pieno di emoji, poiché ci sono persone da tutto il mondo e questi sono comprensibili da tutti. Lì mi venne l’idea di provare a scrivere una storia solamente con gli emoji, così iniziai a collezionarli, e scrissi la storia di una giornata di questo personaggio “mr Black”. Questo libro è stato stampato in diversi paesi, senza bisogno di traduzione.

Ma è davvero un linguaggio universale?

No, certamente bisogna avere dimestichezza con il cellulare per poter comprendere questo linguaggio degli emoji. Forse tutti quelli nati dagli anni ’90 in poi che hanno un cellulare possono comprenderlo. Gli emoji sono ormai utilizzati anche per la segnaletica, pensiamo ai bagni pubblici, alle sigarette, sono uguali ovunque. Credo che siamo in una nuova era del geroglifico.

Ma quanto si perde con questa semplificazione del linguaggio?

Certamente viene meno la bellezza e la profondità del linguaggio originale, ma forse con gli emoji si può raggiungere una bellezza in più, diversa. Ho anche tradotto un’antica poesia cinese molto bella con gli emoji.

In “Background Story”, ha creato una scatola di ombre utilizzando materiali come paglia, erbacce, fiori secchi, rami e rifiuti per sostituire la pittura a inchiostro. I detriti sono usati per creare pennellate. Background Story presenta una tensione dinamica tra quello che lei chiama “l’aspetto esteriore” e il “contenuto interiore” dell’opera per forzare una “comprensione errata dell’oggetto”. Questa confusione è ulteriormente accentuata quando il visitatore esamina il retro del lightbox, che crea l’illusione del paesaggio dipinto, e scopre invece i detriti utilizzati per formarlo.

A proposito di questo tipo di opere lei ha detto che: “queste opere sono come i fantasmi di vecchi dipinti che infestano i musei che occupavano”.

Quando ero bambino la Cina era molto povera, quindi per noi la spazzatura aveva un valore, non si poteva buttare, poteva essere riutilizzata. Ho sempre guardato allo scarto come qualcosa di prezioso; ad esempio per fare una scultura preferisco prendere il marmo avanzato da un’altra scultura. Per le Olimpiadi di Pechino del 2008 si costruirono moltissimi edifici nuovi molto costosi, che furono realizzati materialmente da lavoratori poveri. Poi mi resi conto che queste zone erano piene di spazzatura e quando mi chiesero di realizzare un’opera per le Olimpiadi decisi di usare materiali di scarto per creare una fenice da mettere al centro di uno di questi palazzi. Gli piacque, ma alla fine non l’accettarono.

Lei parla della sua opera “Phoenix Project” esposta all’Arsenale di Venezia qualche anno fa, realizzata con rifiuti e materiali di scarto. È vero che Philippe Petit ha camminato su quell’opera?

Sì, a New York nella chiesa di St. John the Divine Philippe Petit camminò tra le due fenici, ma fu la prima volta che fece una delle sue camminate così in basso, era abituato a grattacieli e altre imprese vertiginose.

Ho trovato di grande interesse anche il suo lavoro “Dragonfly eyes” (2017). Questo enorme sguardo di libellula ci mostra scene di vita quotidiana e incidenti tragici, eventi terribili o divertenti, ma lo spettatore reagisce a entrambi in modo distaccato, freddo, perché freddo è lo sguardo asettico della telecamera di sorveglianza. Questo film/documentario è un’opera senza attori e senza regista, era questa la sua intenzione?

Quando ho fatto questo lavoro l’ho pensato sia in chiave politica che filosofica e sociale. È stata una sorta di risposta al film “The Truman show”, perché penso che ormai stiamo diventando tutti come il protagonista del film, viviamo tutti costantemente dentro a un set cinematografico. L’idea iniziale era di fare un film di finzione, ma non avevo abbastanza materiale. Due anni dopo però ho trovato moltissimo materiale online di persone comuni, che assieme ai miei assistenti abbiamo scaricato con venti computer e visionato pazientemente. Abbiamo lavorato un po’ come Uber, che lavora senza avere macchine ma con le macchine delle persone civili, noi senza macchine da presa e senza cameraman abbiamo utilizzato i dispositivi della gente.

Quanti anni di lavoro ci sono voluti?

6 anni. Ma per due anni ci siamo fermati.

Lei è considerato un artista concettuale, ma nel suo lavoro, oltre all’idea, al concetto, c’è spesso anche un gesto artistico e una conoscenza tecnica. Si riconosce nella definizione di artista concettuale?

All’inizio della mia carriera le mie prime opere di successo le ho fatte perché non prestavo davvero attenzione al sistema dell’arte. Non mi interessavano gli stili, le scuole, le correnti e la storia dell’arte. La mia personale riflessione sull’arte sicuramente non è scaturita da queste cose. Poiché queste cose sono tutte “knowledge”, sono la cultura stessa e l’arte non si può ‘estrarre’ dalla cultura.

Per questo mi ha sempre interessato ciò che stava fuori dal sistema artistico, mi interessava davvero vedere cosa succedeva lì fuori, nella società. Nella società le cose poi cambiano rapidamente, soprattutto oggi. Questi cambiamenti a volte avvengono al di fuori delle nostre categorie concettuali. In questo modo, se fai attenzione al ‘fuori’ si mettono in luce delle problematiche nuove e come artista devi provare a rifletterci su e ad affrontarle. Al contrario l’arte dei grandi maestri del passato oggi è completamente inutile e inefficace ad affrontare i problemi contemporanei.

Ma le domande essenziali dell’uomo non sono sempre le stesse?

In parte sì, ma ci sono oggi nuovi quesiti e nuovi problemi che fino a tempi recenti non erano proprio considerati, questioni legate alle nuove tecnologie. Attualmente c’è una mia mostra a Venezia chiamata “Art Satellite”, una cosa totalmente nuova che non esisteva prima, non esisteva proprio il termine.

Lei è tornato a riflettere sul linguaggio nel suo ultimo lavoro “Art Satellite. The First Animated Film Shot in Space”, (2024); nel video in stop motion ritorna l’omino (Mr. Black) del “Book from the ground”, che cerca di trovare un linguaggio universale proprio mentre il satellite orbita intorno alla terra attraversando confini linguistici e politici.

È stato complesso creare questa prima opera d’arte spaziale? Ci sarà un futuro per questo tipo di opere d’arte?

È stata una società privata di satelliti che mi ha chiesto se volessi realizzare un’opera con uno dei loro satelliti. Facemmo un tentativo che però non andò bene e il satellite si distrusse a terra. Subito dopo molte società private mi chiesero se volessi realizzare un’opera per i loro satelliti. Decisi quindi di fare un’animazione con mr black per riflettere del linguaggio nello spazio; le lingue dello spazio sono solo l’inglese e il russo. Lo spazio è un luogo interessante di sperimentazione, non ci sono ancora leggi, e guardare allo spazio in fondo è come guardare tramite un riflesso quello che avviene sulla terra. Lo spazio è un po’ la nuova America, c’è una grande corsa e tutti vogliono accaparrarsi il proprio posto.

La scrittura e il linguaggio sono temi centrali nella sua produzione. Quale libro è stato più importante nella sua vita?

Non saprei, è una domanda difficile. Credo di non poter rispondere… il libro rosso? (ridiamo). C’è un altro libro per me molto importante a dire il vero; quando ero a New York mi colpì molto una signora un giorno nella metro, perché andò via la luce e tutti si preoccuparono, mentre lei era impassibile e continuava a leggere il suo libro. Era una persona cieca, e il libro era scritto in caratteri braille. Si era ribaltata la situazione. Alla fine quando dovette scendere si alzò, io mi ero addormentato. Mi svegliò e mi regalò il libro. Rimasi molto impressionato e sono molto legato a quel libro.

English version

Recognition for an artist is often a matter of central importance. Finding one’s own language, a style that distinguishes them and makes them recognisable among many, is what has made many artists famous, especially in the past two centuries. Then there are those who do not remain locked in self-definition, in the repetition of their style ad infinitum, but who change in an almost metamorphic manner. This small group undoubtedly includes the artist Xu-Bing, one of the best known and most successful Chinese artists in the world. While there is certainly a common thread linking his research and his artistic process, looking at his catalogue one can easily fall into deception and believe that these are works by different artists, such is the diversity of approaches, languages, techniques and materials used. Indeed, Xu-Bing has developed a kind of style without style. His work draws from both his own personal past and the archaic past of his country, while also engaging in dialogue with Western art and thought. It is perhaps this encounter between East and West that has aroused such unanimous approval; Xu-Bing’s work is in fact now at home in major American and European museums (the Metropolitan and the British Museum among others) and is appreciated by leading Western philosophers such as Derrida, with whom he has also lectured in New York.

We met the master in Venice during the first days of the LX edition of the Art Biennale, where he opened his solo exhibition ‘Art Satellite. The first animated film shot in space’, curated by Sen Fu with the collaboration of Giovanni Argan and Yiping, which can be visited until 7 October in the Church of Saints Jeremiah and Lucy. Echoing the inscription on the back of the church’s apse ‘To Italy, to the world, implore light, peace’, the artist presented an avant-garde work of video art with a futuristic flavour in the Chapel of St. Veneranda, being in fact the first ever to have been shot in space. It is a short video showing a stop-motion animation film projected onto a screen of the Ladybug No. 1 satellite as it orbits the Earth. The satellite, a medium mainly used for scientific, military and communication purposes, becomes an artistic instrument for the first time, and by going beyond terrestrial borders, beyond barriers and walls, the problem of language so dear to the artist becomes universal.

After a few weeks, we have an appointment with the artist in Rome, at the American Academy, where he inaugurated the exhibition ‘A Moment in Time: Xu Bing in Rome’ (curated by Ilaria Puri Purini and Andrew Heiskell) at the end of his residency at the institute. Here, a cast of the Great Wall of China, created by the artist in 1988 using the traditional technique of frottage, dialogues with a cast of the Appian Way made especially for the installation, called ‘The Wall and the Road (1988-2024)’.

The Chinese and Roman empires, two great civilisations thousands of years old, meet, on the one hand with a wall that served to protect, encircle and delimit, and on the other with a road, the regina viarum, emblem of openness and encounter with the other. Built about a century apart, from 214 B.C. by the emperor Qin Shi Huang the wall, and from 312 B.C. the road at the behest of the censor Appius Claudius Blind, the road and the wall, still perfectly preserved, are taken in their skin by the artist. Isolated and seen up close, these casts have their own dimension and the Appian Way, with its large stones set into it, looks like the spotted skin of a feline and elicits an almost alienating effect, a reaction typical of many of his works.

Two important exhibitions open at the same time in Italy that give the measure of the importance of this artist, who has made language and sign motives for investigation and profound reflection in his artistic research.

In the garden of the American academy, while a thunderstorm roars in the background keeping us on the alert, we begin our long conversation, switching from Chinese to English to Italian, with the help of the young curator Sen Fu.

Let’s start by talking about one of the main themes of your artistic research: language. Chinese calligraphy is an art form also included in the Unesco intangible heritage list. With your work “Book from the sky” you created over 4000 fake Chinese characters, very similar to the real ones, deceiving visitors. Was that a reflection on language? On its importance, on its ability to influence culture and society itself?

Many of my works are related to writing and language. I never chose or planned this, it came naturally. The direction each artist takes is not controllable by him or herself, nor can it really be planned. It all happens by a kind of predestination, of karma. Each artist does not like his own style, his own expressive language, but loves that of others. Your personal language and style, if they really belong to you, you cannot eliminate them. If you look at Chinese writing, you understand Chinese culture. My mother worked in the university library, and as a child I lived in there and looked at the books without understanding, fascinated though I was by this writing. When I learned to read then it was the time of the Cultural Revolution and there were no more books we could read, the only one was Mao’s Red Book. So I always had a very special contact with books and words. Writing has had great power in the history of mankind; when there was an emperor in China, one could get into serious trouble even for writing an unwelcome word. Problems that my father also had at the time of the Cultural Revolution; when I was a child, I saw my father’s name appear on a dazibao and on it was written that he was a counterrevolutionary/reactionary. There I understood the power of writing. There I understood the power of writing. It is no coincidence that all Chinese emperors when they came to power the first thing they did was to change their writing immediately. When they changed the writing I think they also changed people’s mentality and thinking.

In this effort to understand something unreadable there is something ironic, also suggested by the title of the work, which is perhaps meant to evoke the sacred scriptures? “in the beginning was the verb”…

This work of mine has a distinguishing feature: I want the thread of thought of the people who see it to be interrupted, to remain as if stuck, trapped.

As they approach ‘Book from the sky’ they think it is a monumental book with its engraved characters that perhaps speaks about the great themes of life, but then they cannot read it, and at that moment they start to wonder about books and culture.

I find of special interest “A Case Study of Transference”, where the most carnal instincts were staged by pigs trying to mate, contrasted with the writing on their bodies and the writing on the books on the ground.

It is an apparently very different work, but basically very close to ‘Book from the sky’. I have always been interested in performance, but being very shy I used a few actors, in this case animals, and even the characters on the pigs’ skin meant nothing. The most interesting aspect was the reactions that these pigs trying to mate aroused in the spectators, who were ashamed, felt very embarrassed, whereas for pigs everything was normal. Humans have these characters, i.e. culture, engraved not on their outer skin but inside their bodies.

With the Book from the ground (2003) you tried to invent a language from scratch that everyone could understand with emoticons, a universal Esperanto. How did this book come about?

There was a time when I travelled a lot, so I was spending a lot of time in airports, where it is full of emoji, because there are people from all over the world and they are understood by everyone. There I got the idea of trying to write a story just with emoji, so I started collecting them, and wrote the story of a day of this character ‘Mr Black’. This book has been printed in several countries, without the need for translation.

But is it really a universal language?

No, certainly one has to be familiar with a mobile phone to be able to understand this emoji language. Perhaps everyone born since the 1990s who has a mobile phone can understand it. Emoji are now also used for signage, think of public toilets, cigarettes, they are the same everywhere. I think we are in a new age of hieroglyphics.

But how much is lost with this simplification of language?

Certainly the beauty and depth of the original language is lost, but perhaps with emoji one can achieve an extra, different beauty. I also translated a very beautiful ancient Chinese poem with emoji.

In “Background Story”, you have created a shadow box using materials like straw, weeds, dried flowers, branches, and garbage to substitute for ink painting. The debris is used to create brushstrokes. Background Story has a dynamic tension between what you call “the outward appearance” and “inner content” of the work in order to force a “faulty understanding of the object.” This confusion is further enhanced once the visitor examines the back of the lightbox, which creates the illusion of the landscape painting, and instead discovers the debris used to form it.

About this kind of works you said: “these works are like the ghosts of old paintings haunting the museums they used to occupy”.

When I was a child, China was very poor, so for us rubbish had a value, it could not be thrown away, it could be reused. I have always looked at waste as something valuable; for example, to make a sculpture I prefer to take the leftover marble from another sculpture. For the 2008 Beijing Olympics, a lot of very expensive new buildings were constructed, which were materially made by poor workers. Then I realised that these areas were full of rubbish and when they asked me to make a work for the Olympics I decided to use waste materials to create a phoenix to put in the centre of one of these buildings. They liked it, but in the end they did not accept it.

You are talking about your work “Phoenix Project” exhibited at the Arsenale in Venice some years ago, made from rubbish and waste material. Is it true that Philippe Petit walked on that work?

Yes, in New York in the church of St. John the Divine Philippe Petit walked between the two phoenixes, but it was the first time he did one of his walks so low, he was used to skyscrapers and other dizzying feats.

I also found your work of great interest “Dragonfly eyes”, (2017). This huge dragonfly gaze shows us scenes of everyday life and tragic incidents, terrible events or funny events, but the viewer reacts to both in a detached, cold way, because cold is the aseptic gaze of the surveillance camera. This film/documentary is a work without actors and without a director, was that your intention?

When I did this work, I thought of it from a political as well as a philosophical and social point of view. It was a kind of response to the film The Truman show, because I think we are all becoming like the protagonist of the film now, we are all constantly living inside a film set. The initial idea was to make a fictional film, but I didn’t have enough material. Two years later, however, I found a lot of material online from ordinary people, which I and my assistants downloaded with twenty computers and patiently watched. We worked a bit like Uber, which works without having cars but with the cars of civilised people, we without cameras and without cameramen used people’s devices.

How many years of work did it take?

Six years. But for two years we stopped.

You are considered a conceptual artist, but in your work, besides the idea, the concept, there is also often an artistic gesture and technical knowledge. Do you recognise yourself in the definition of conceptual artist?

At the beginning of my career, I made my first successful works because I did not really pay attention to the art system. I was not interested in styles, schools, currents and art history. My personal reflection on art certainly did not stem from these things. Because these things are all ‘knowledge’, they are culture itself, and art cannot be ‘extracted’ from culture.

That is why I was always interested in what was outside the art system, I was really interested to see what was going on out there, in society. In society things change rapidly, especially today. These changes sometimes happen outside our conceptual categories. So if you pay attention to the ‘outside’, new issues come to light and as an artist you have to try to think about them and deal with them. In contrast, the art of the great masters of the past today is completely useless and ineffective in addressing contemporary problems.

But aren’t the essential questions of man always the same?

In part yes, but there are now new questions and new problems that until recently were not really considered, questions related to new technologies. There is currently an exhibition of mine in Venice called ‘Art Satellite’, a totally new thing that did not exist before, the term did not exist at all.

You have returned to thinking about language in your latest work “Art Satellite. The First Animated Film Shot in Space”, (2024); in the stop motion video the little man (Mr. Black) from the book from the ground returns, and is trying to find a universal language just as the satellite orbits the earth crossing linguistic and political boundaries.

Was it complex to create this first work of space art? Will there be a future for this type of artwork?

It was a private satellite company that asked me if I wanted to make a work with one of their satellites. We made an attempt, but it did not go well and the satellite was destroyed on the ground. Soon after, many private companies asked me if I wanted to make a work for their satellites. So I decided to make an animation with Mr Black to reflect on language in space; the languages of space are only English and Russian. Space is an interesting place for experimentation, there are no laws yet, and looking at space is basically like looking through a reflection at what is happening on earth. Space is a bit like the new America, there is a big race and everyone wants to grab their place.

Writing and language are central themes in his production. Which book has been most important in your life?

I don’t know, it’s a difficult question. I guess I can’t answer… the red book? (laughs). There’s another book that’s very important to me actually; when I was in New York I was very impressed by a lady one day in the underground, because the lights went out and everybody got worried, while she was impassive and kept reading her book. She was a blind person, and the book was written in Braille. The situation was reversed. Finally when she had to come downstairs she got up, I had fallen asleep. He woke me up and gave me the book. I was very impressed and I am very attached to that book.

Si ringrazia Valentino Eletti per l’aiuto fornitomi nella traduzione dal cinese.