Descrizione

Storia dell’arte 9/10, Gennaio – Giugno 1971

Maurizio Calvesi

Caravaggio o la ricerca della salvazione

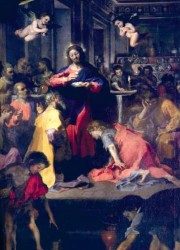

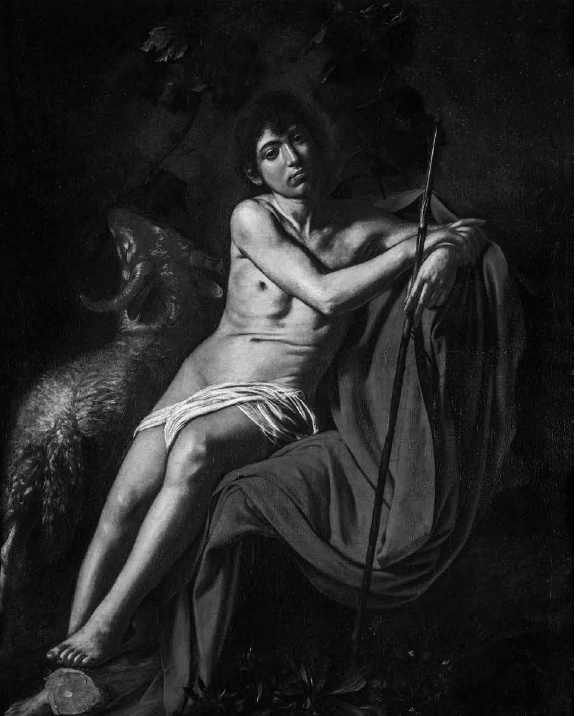

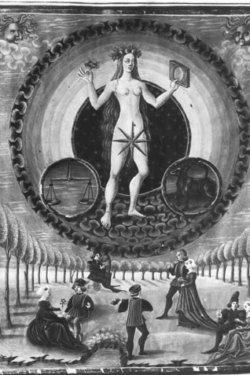

Caravaggio, like the painters of the Renaissance, still sees the world as a symbol, and nature and history as messages to be deciphered.The author, following his previous interpretation of the « Boy with a basket of fruit » as a representation of Love, explains several of the youthful paintings of Caravaggio as Christological allegories. The «Boy with a basket of fruit» is in fact Christ as Love bringing eternal life, the «Bacchus» of the Uffizi is the Redeemer with the attributes of Dionysius, symbols of the resurrection, in the act of offering the chalice with the symbolic wine of his blood. The «Boy peeling a pear », when compared to an engraving by Lucas of Leyden, is seen as Christ redeeming humanity from original sin. The «Young Bacchus» is a Redeemer with the symbols of death (black grapes) and of the resurrection and eternai life (evergreen wreath ). The basket with the apples and grapes as a symbol of the resurrection appears also in a stili life by H. Steenwyck. The symbols of the eucharistic bread and wine are found again in the two versions of the «Supper at Ernmaus» and in the London version are associated with the roasted bird and the basket of grapes, the apples and the pomegranate. The same symbols (bread, wine, grapes,apples, pomegranate and dead birds) appear in the so-called «Payment» by Lucas Cranach, interpretable by alchemical code as an allegory of the conjunction of male and female. The youthful and androgynous character of Caravaggio’s models is accordance with a symbolic purpose and alludes to Eternity and Love portrayed as harmony and conjunction. The same symbol is also expressed by music and with this key one can interpret «The Lute Player » in Leningrad and the «Musica». The author then traces, through the Pellizzari frieze by Giorgione and through several still lives of the Leyden School of the 17th century, symbols of musical instruments and of weapons and armour alluding to love and virtue, or to virtuous and steadfast love (the constant view- point of the lute alludes to steadfastness) and on the basis of these symbols Caravaggio’s «Victorious Love» is explained. This painting is then related, iconographically, to a print by Agostino Carracci representing «The old man and the courtesan». In the «Mary Magdalen» are found the characteristics both of vanitas and of melancholy. «The boy bitten by a lizard» is alto interpreted as a representation of vanitas — comparing it to the «Gentleman in the studio » by Lorenzo Lotto and to a stili life by David Bailly. Finally the author sees a source of Caravaggio’s youthful invention in Greek and paleochristian sculpture, and notices a precedent set by the allegorical «Old woman» by Giorgione.

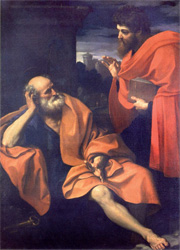

Further, the author connects the theme of love and redemption to that of Grace, a central argument in the Agustinian doctrine and a bone of contention between Catholics ami Protestants; the «Calling of St. Mathew» is inspired by the theme of Grace as is also the «Conversion of St. Paul». Caravaggio’s light seems lo have a theological meaning which alludes above all to the Grace that extracts humanity from the shadows of evil. The theme of Grace as transmitted by the Church is the inspiration of the Madonna of Loreto in the Church of Santo Agostino, the Martyrdom and the Calling of St. Mathew, as well as the Fall of St. Paul. In addition to the literal meaning, the religious paintings by Caravaggio seem to contain an allegorical meaning which confers a certain suspension to the setting: the Crucifixion of St. Peter alludes to the edification of the Church of Martyrdom, the Vatican Deposition is an allegory of the Church founded on Christ as «corner stone»; the Death of the Madonna refers to the Church as the eternal bearer of Grace; the Decapitation of St. John to the Sacrament of Baptism. The author connects some themes of the Caravaggian concept, including the motive of «night» as sin and light as salvation, in the environment of Charles and Frederick Borromeo, to whom is also connected Simone Peterzano, the author of the Flagellation of Santa Prassede, in which we already find the allegorical suspension and the motive of «night». Other points in common with Frederick Borromeo, who was later to protect Caravaggio in Rome, can be deduced from the treatment of De Pictura Sacra. On the whole Caravaggio should be seen as representative of the Counter Reform, His misfortune is related to the election of Pope Paul V and with the interruption of the policy of which Borromeo had been the supporter.